giardino all’oscuro

Davide Rivalta

26.01.2024 – 01.04.2024

Garden in the dark

A conversation between Davide Rivalta and Miral Rivalta

The title of this exhibition is taken from Pia Pera’s book, To the garden I haven’t told it yet, inspired by Emily Dickinson’s poem Non l’ho ancora detto al mio giardino. The author, the protagonist of her narrative, who is ill with ALS, suggests through her experiences and physical exertions in her months of infirmity that one day the gardener (i.e., she) will not keep her appointment with the place she has fashioned. Page after page she gains more and more awareness about her condition; one day she will be forced to abandon her garden. As her illness progresses and prevents her from caring for it as she would like the park changes in parallel.

In these months, another garden will take over the spaces of Fuocherello, that of Davide Rivalta. As I pondered this exhibition and what to write about it, after years of working together with my father it is safe to say that I have in mind the detailed monologue about his sculptural poetics and practice that I tell the press, collectors, and colleagues. Despite this, and my fondness for his painterly work (in fact, the only work of his that I own is a large painting representing an eagle), I find myself knowing very little about the origin of these works. So, one afternoon, as we both sit at our desks in the office of the de Carli Art Foundry, I take advantage of a particularly quiet moment at work to ask him a few questions, and ask him what his painting originated from.

Q: When I was working on the sculpture of the first Indian Rhinoceros used to use clay powder that created a myriad of shades and colors on the surface of the sculptures, I thought the same process could be applied to painting using pigment powder.

M: One of the most unique and recognizable features of your work is the physicality with which you approach the subject matter.

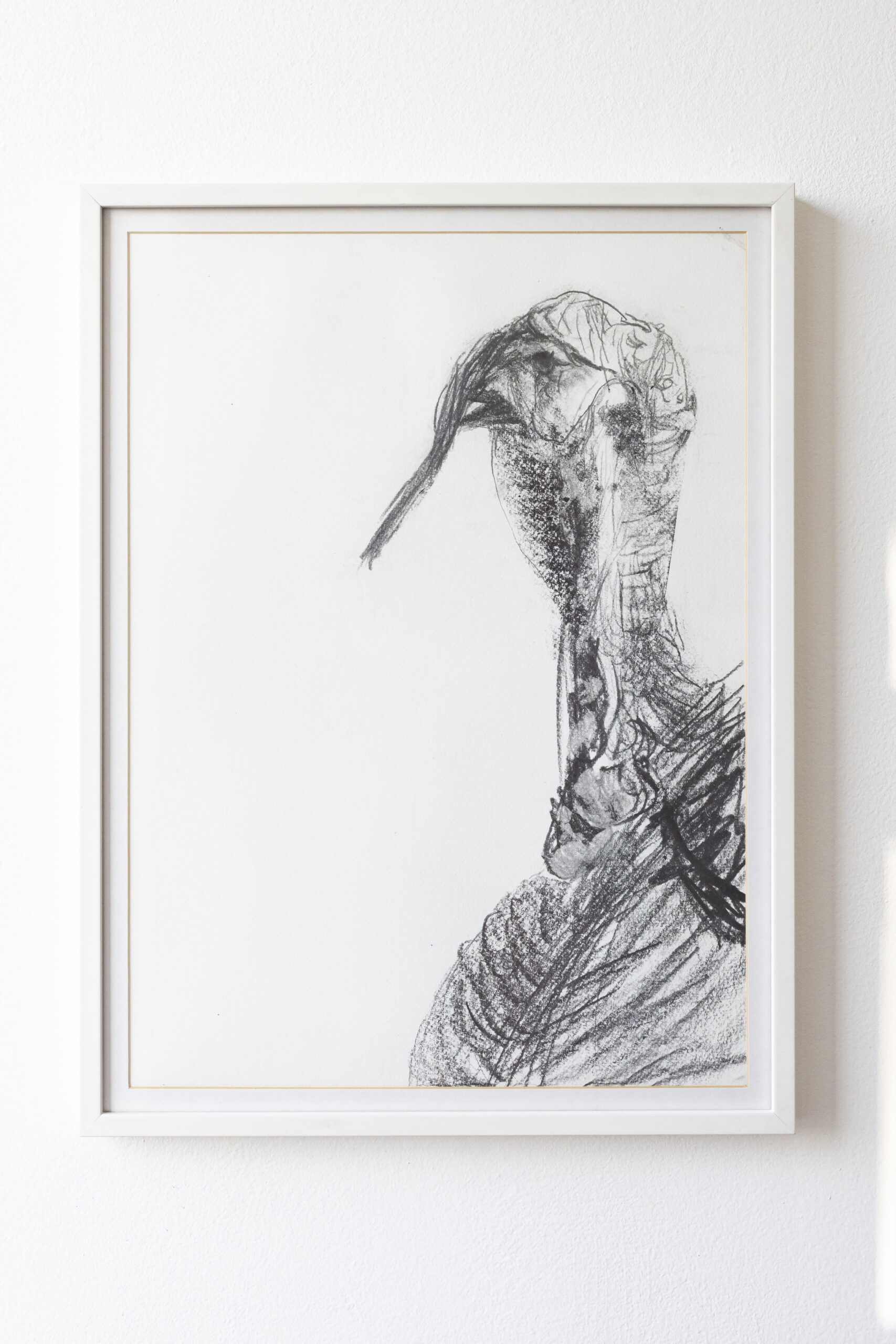

Q: Yes, when I sculpt I throw clay, in the same way I throw color. My way of working is very instinctive and I usually reason by masses and volumes. Even the tools I use are often tools of sculpture, to make asparagus and tomatoes I use rubber molds, I mix the oil color with the same mixer with which I soften the clay. I have even happened to use the hose to smooth hardened paint surfaces. Another element that I am very interested in, and that has to do with sculpture as a three-dimensional object, is gravity. I am interested in the gravity of the pictorial mass and the gravity of the subjects I portray. The sprouting vegetable tends upward while the animal, downward. So in this exhibition there are opposing forces. I had been interested in the theme of the vegetable cultivated for food because it seemed to me to be a subject strongly related to human survival and, at the same time, I am fascinated by the wonder of watching an asparagus or a zucchini flower sprout. Instead, for the painted animals, as then also for the modeled ones, I start by being interested only in the figure; only later do I place the sculptures in the landscape. I began to work on backgrounds only after several years, looking for this relationship so fundamental in the history of painting between figure and background. It happens naturally for me to create animals that appear suspended, or jumping. In a circumscribed space that is in no way defined prospectively and becomes more or less ethereal matter.

M: I think it is for this reason that the exhibition appears cohesive. The animals don’t seem out of place next to your ‘vegetable’ painting. It is as if your little ‘vegetable gardens’ fill the void given by the abstraction of the background.

Q: Yes, it can be.

M: You often refer to your sculptural works as portraits of real animals that you have encountered in captivity and photographed yourself and then reproduced them three-dimensionally, is the same true for paintings?

Q: Yes, my painting also always starts from a photographic image. The eagles all from the same photograph, although they are very different paintings, and the rottweilers from other photos I have taken over the years. They are studies, about how the figure, animal or plant, rests on the ground, or is suspended in space.

M: I think it’s also worth adding a few words about why we are here. You and I, father and daughter and just in Fuocherello with a painting exhibition of yours. If it’s okay with you I would start by making a couple of introductions. We’ve been working together on different projects for a few years now, and I’d say we make a good team! In terms of why here and now you have to remember that Fuocherello began as an exhibition project focused on sculpture. Despite this, after a year and a few months of almost entirely sculptural programming I felt a great need to show some painting and, yours, so sculptural it seemed to me the most congruent introduction with our project and the context in which the gallery is located. What did you think?

Q: Yes, Fuocherello is a project born mainly out of passion and a desire to do research on sculpture. The desire of Manlio Bonetto, Andrea Tolardo, Piero De Carli and Philippe Jacopin acted as a fuse and allowed Fuocherello to become, a space of investigation into sculptural materials and practices. My painting I think has a lot to do with these elements, through painting I fully address discourses and reasoning about sculpture.

M: I’ve always cared about the gallery being especially focused on young talent. You are not very young, however, I am very passionate about the idea of showing a little-known side of your artistic practice. In fact, I believe this is one of your first exhibitions (if not the first) to feature exclusively two-dimensional works. Then again, the first exhibition I hosted at Fuocherello as director was a solo show of Emaneuele Becheri, after his ‘renaissance’ as a sculptor.

Davide Rivalta’s garden is made of abstraction. It is a garden in which vegetables and flowers are easily distinguishable, almost three-dimensional and realistic, but they sport seemingly improbable colors and are placed in unrecognizable fields, surrounded by animals foreign to agriculture. The forms, textural that emerge from her canvases are entirely done in oil paint, and dusted, “fertilized,” with pigment. Thus I am reminded of Pia Pera and the concept of abandonment by the gardener. Davide’s gardens, his vegetable gardens, are used to being abandoned and recovered after years. He in fact prefers sculpture and due to practical contingencies devotes very little time to painting practice. In addition, the thickness of his paintings causes very long drying times. For example, the painting of tomatoes that I had used for the exhibition communication has an almost unthinkable weight for a pictorial work of that size, and it took years to dry. In fact, on the day we placed it upright to decide on the exhibition layout a tomato, like a real fruit past its ripening point, succumbed to its own weight, and not being completely dry it fell off. After reattaching the yielded element with oil paint, we said to ourselves that it will be for next time, placing it once again in its crate, not knowing when the next time will be and whether it will hold up, sooner or later, to the gravity that fascinates David so much.