In Levare

FrancescoCarone, Maria Deval

In Levare

Text by Emanuele Becheri

Has the excellent artist no concept

there a marble alone in himself does not circumscribe

With his superego, and only that comes

The man who obeys the intellect

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1538)

In Levare è il titolo della mostra che raccoglie le opere di due artisti, Francesco Carone e Maria Deval. Lo spazio di Fuocherello di Volvera accoglie al suo interno cinque sculture e una stampa tratta da una matrice xilografica in legno di ciliegio. I due artisti nel corso della propria ricerca si sono cimentati con la scultura, ma il tratto che caratterizza questi specifici lavori in mostra è la pratica della scultura a taglio diretto.

In Levare is the consummate appearance of the image from the block, a plastic adventure that differs from modelling or any other techne and perhaps the oldest practice of sculpting: essentially a journey with no return, where, when you carve, you carve forever.

Before this decisive intentionality there was only the stone and the tree standing out in the landscape.

By Francesco Carone, the first work that struck me was the sculpted portrait of an hazelnut (Nocciolo, 2012) – I later learned – carved from the branch by the same plant that had generated it (a peach tree in blossom). In fact a sculpture with a real specific weight, which demanded to be looked at carefully. The virtuous circle that Francis had triggered widened my gaze on that sculpture; but what stayed with me most was that presence, that deposed kernel: its small monumental dimension contained the seed of sculpting.

Whereas by Maria Deval I saw a head for the first time two years ago. Forced to approach it because of its size on the edge of the visible, I saw the decisiveness of the gaze: what was present had no form, it literally came out of the sculpture, it generated a landscape. The gaze of the sculpture.

Like blowing from time.

I later learned that that head, which she calls Selva, had been carved out of a hazel.

I wonder what temperament these two artists come from today, their stubbornness to strip away the superfluous from the mass, to make a material alive or dead with chisel strokes.

When I look at their works, I have the perception of seeing the two artists in the act of sculpting. I don’t know if this ghost is a value, an obscurity or the value of these sculptures themselves, but certainly these former materials seem definitively alive.

If we see the sculpture Transverberation (2016), we might as well not even know that it was carved from a mass-produced object in 1962 . Indeed, what emerges on seeing it is the tension of a human figure sinking into the marble: unexpected veins draw its masses, unfinished rough-hewn shapes suggest vague forms. Of the figure, the left limbs – arched into the block almost as if they wanted to come out – act as a counterpoint to the right hand, which covers the wound in the middle of the legs: by focussing the gaze on what cannot be seen and which is perhaps the material of which the work is made, the artist reawakens the object in sculpture.

Leaning on a shelf jutting from the wall is a wooden carving (Bastet, 2024): a waiting feline figure that recalls plastic echoes and suggestions and that the name – vast in meaning and contradictory over the centuries – reinforces but does not reveal. We are in front of it, or rather, we are obliged to bow down to its size in order to see its details; but when we move away from the lines and masses that constitute it, this solemn posture of the body, carved from the same block on a hypothetical plinth, produces a gaze that goes far beyond the lines and masses that make it up.

Golgota (2021) is a block of carved mahogany, exposed to the ground: a rounded whole rough-hewn with a chainsaw and then detailed with a chisel into wide, rounded leaves, as if stormed by the sea. Perhaps not by chance, Francesco Carone in the parenthesis following the title Golgota uses the specification ‘rock’ (a reference, the sea, present throughout his poetics).

The sea, a great sculptor, consumes everything that its force laps.

And if we go and look at the seed of the words that make up the word ‘Golgotha’, we discover that they have meanings relating to ‘being round, circular’; certainly the artist has taken this into account, making the phonè coincide with the forms.

But this Golgotha has a peculiarity that differentiates it from the canon and makes it unique: a sculpted fringe sits as if lying on top of it, scarring the hollow that should have held the wood of the Cross.

What remains is a Golgotha, a Calvary, and indeed the site of the Skull. Rock lashed by the waves.

Profilo (2024). On the cut of a splinter of wood emerges a half-bust with barely visible satirical features, sketched in by the chisel strokes alone; features that are at one with the architectural momentum of the splinter. Sharp is its profile.

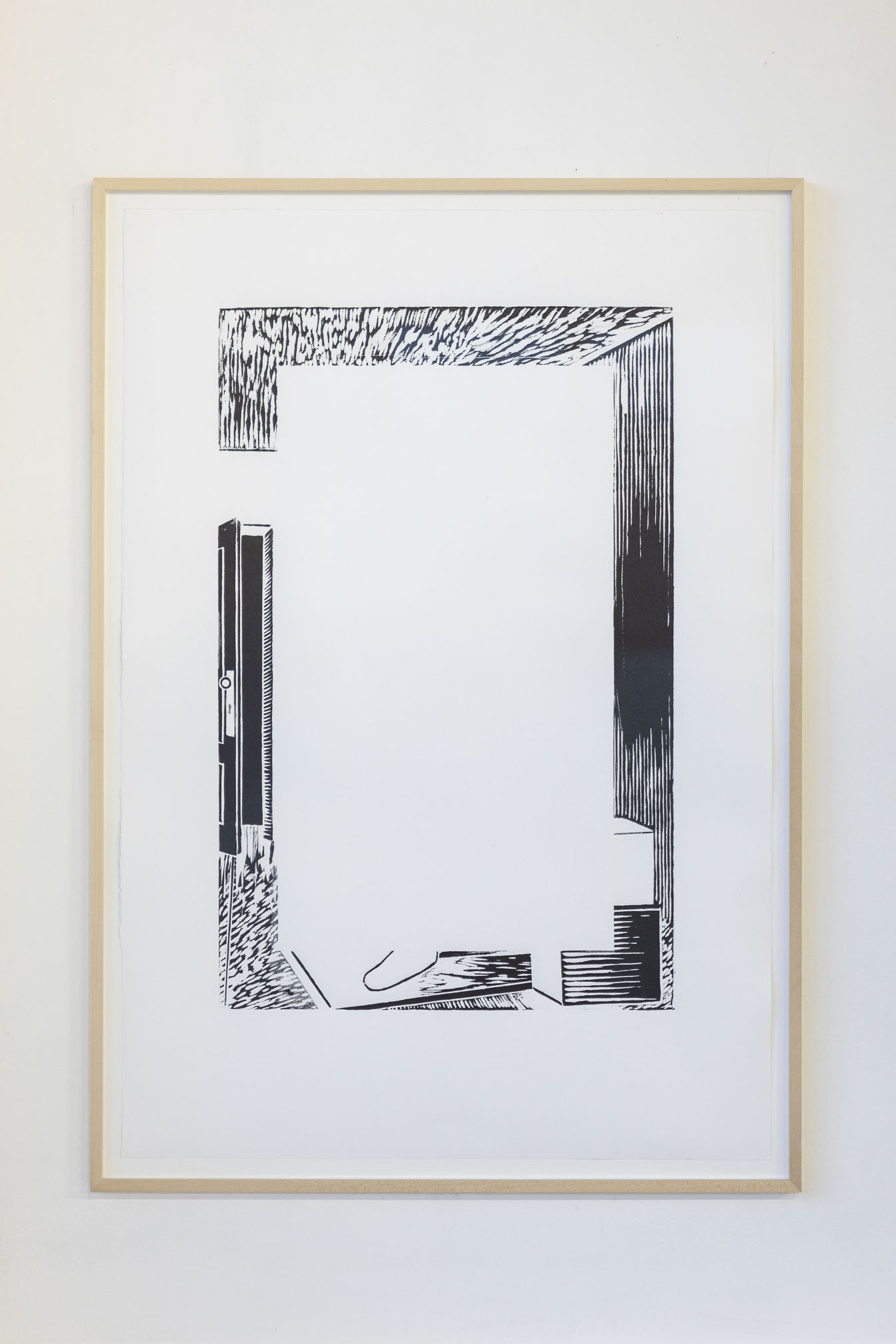

Adoratore (2016) is a carved frame reproducing the outer margin (on a 1:1 scale) of the L’idolo Ermafrodito, by Carlo Carrà (1917), subsequently inked to make woodcut prints on paper, one of which is on display without its matrix. Thus, the artist constructed a cherry wood frame – it is no coincidence that the hardness of the cherry wood is traditionally suited both for making frames and carvings from it – by carving the portion of Carrà’s work in reverse, so as to obtain in print the reverse side of the image of the original painting. The images that result from this printed ‘frame’ are architectural hints that border on purely abstract parts and others that indicate precise spaces present in the original. The artist subtracts the essential scene – the hermaphrodite mannequin painted by Carrà in the centre of the painting – to emphasise openings and thresholds, leaving a barely ajar door from the window-frame where darkness can be glimpsed.

Maree(2024). Found on the beach by the remnants of a fire, the wooden particle was carved into the essential sinews just enough to make it leap out of its original condition.

eb.